Ashawaug Farm Preserves Indigenous Crops and Crafts

Dawn and Cassius Spears host learning workshops for seed saving and flower drying while growing Narragansett Flint Corn, the "three sisters," and more than forty heirloom varieties of tomatoes.

Tomato season may be long over, but at Ashawaug Farm in Ashaway, Rhode Island, squash harvesting and seed saving is just beginning. The focus here is on cultivating more than forty varieties of heirloom tomatoes, plus Narragansett Flint Corn, squash and beans – known as “the three sisters” in the Indigenous community. The small-scale commercial heritage farm specializes in heirloom, culturally relevant and Indigenous varieties of vegetables and it serves as an outdoor educational classroom to teach workshops in seed saving, floral preservation and art.

The land is cared for – notice I didn’t say owned – by an Indigenous family, Dawn and Cassius Spears, and their children and grandchildren, who grow with love and respect for the land. Their six-acre parcel is part of the homelands of the Narragansett-Niantic Tribal community, and it is also the home of the Narragansett Food Sovereignty Initiative and the Northeast Indigenous Arts Alliance.

On an early October day, driving up to the rose-pink-painted homestead, located off Ashaway’s Main Street, there’s a small, welcoming shed that serves as an honor system farmstand. Guests can stop in to purchase whatever produce is in season at the moment along with bouquets of dried flowers. On the day of my visit, the end of tomato season marks representatives of more than twenty different varieties – from Pink Oxheart (bulky and looks just like its namesake) and Black Pear to Speckled Peach (small, round and fuzzy) and Rebel Starfighter Prime (sounds like Star Wars to me). Shelves are lined with a beautiful assortment of honeynut and butternut squash, eggplant and hot peppers, and bouquets of dried flowers hang around the perimeter of the ceiling.

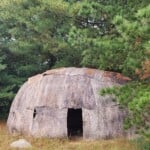

Outdoors, beyond the shed, there’s a field that was once resplendent with corn stalks, tomato plants, squash, beans, herbs, flowers and more, now approaching the end of the season. Two large high tunnel hoop houses also stand in the distance, where they grow tomatoes, peppers and other plants into the colder months. Excess tomatoes are just starting to rot off the vines – if not plucked and eaten quickly – but now the preserving and seed saving begins. Corn varieties are drying straight off the stalks in beautiful colors of golden yellow and crimson (the Strawberry Popcorn variety of corn). Off in the distance along the forest treeline is a wetu, a traditional Native American dome house usually created out of tree bark that provides shelter from the elements. A high fence borders the entire property in an effort to keep deer out.

Dawn Spears walks down the garden plot, past the tomatoes. eggplant and kale, to an area that is cultivating the “three sisters.” The Indigenous term means that the three different varieties of plants support each other as they grow.

“It’s a companion planting. So three sisters, they grow together,” Dawn Spears says. “ You plant the corn, which gets up high, and then you plant the beans, and you have to wait until the corn gets to a certain height before you plant the squash. The leaves of the squash will keep away pests, because they have prickers on them, and then the beans trail up the corn stalk.”

There’s a lot of thought that goes into growing corn in the Indigenous community. “When you grow this corn, we say one-third of it is for you to eat, one-third of it is for you to grow more, and one-third of it is for you to share. I try to make sure I tell everybody that, because I think we forget that in our culture today, we’re not better than, we’re not above, we are supposed to be the same.”

“And I tell my kids, when you look in the corn, and you see how they’re growing, they’re holding each other up,” she adds.

Near the high tunnels is Ashawaug Farm’s outdoor classroom with picnic tables and a building where seed saving, flower and herb drying and art projects take place. The building was constructed thanks to a LASA (Local Agriculture and Seafood Act) grant through the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Division of Agriculture.

“We like to come and learn and share. So I don’t like to say ‘teaching space.’ I like to say more of a sharing space,” Dawn Spears says. “Everything that I’m doing, I feel like it’s something that I want to be able to share. So, the seed saving, and when the flowers are growing, it’s a perfect art opportunity.”

She also uses the land to teach her three children and eight grandchildren about their native Narragansett ancestors. “Watching the plants and seeing how they grow, I like to spark my grandchildren to pay attention to what the plants are telling you,” she says.

On a wooden table inside the building is a pile of dark purple Narragansett Succotash beans, which look almost the same purple as the underside of a quahog shell. “I’m excited about this, because I only was able to grow a few of them last year,” Dawn says. “And this means that next year, I can grow even more, and I’ll keep building up so I can get this back into our diet as a regular food.”

A garland of dried marigolds hangs from the ceiling, created by Dawn and her five-year-old granddaughter. Another table displays dried calendula. She is harvesting the extracts from the flowers using sweet almond oil, which will create a natural skincare product. Several corn husk dolls are displayed in vivid colors, and posters of Spears’ artwork are on display, featuring Indigenous women that resemble mountains built into the earth.

Dawn Spears feels that the Indigenous crops they plant at Ashawaug Farm are like members of their family. She and her husband, Cassius Spears, used to manage the Narragansett tribe’s farm, where they planted Narragansett Flint Corn in a community space for the first time. “That was very significant, because it was being grown on a communal property owned by the tribe, and operated by the tribe. So, it was for us, by us,” she says.

Dawn recounts how the whole community, including the children, helped to harvest that Narragansett flint corn. And Dawn’s grandmother – who was 100 at the time – was there, and she had never done that before. “My husband and I planted it. We had never had that in our community in her lifetime of 100 years. So it was significant,” Dawn says, “but the thing that really would get me, is when you went up to the edge of the corn, and if you just stood there, you could feel the energy coming off it.”

It was almost like the corn was holding the memories of their ancestors in the way the stalks swayed and rustled in the wind. “We had a Food Summit in 2018 and I had a couple of [Indigenous] ladies that came, and I said, just go stand by the corn. So they went, and I didn’t tell them what to expect,’” Dawn says. “They came back a few minutes later, and tears were streaming down their faces.”

Dawn continues, “We have ties to this land that predate everybody else, and people like to act like that’s not the case, but it is the case,” she says, biting back tears of her own. “What we are feeling is so much more intense and deeper. Something like that corn being brought up from the earth…that is our ancestors. They put the love in that corn so that it could come back…so we have to keep doing this.”

Ashawaug Farm, 120 Main St., Ashaway, ashawaugproject.com