First Person: Fantasy Island

From 'bluegrass' to famous fromage, people abroad harbor all kinds of misconceptions about the Ocean State.

I’ve scoured the web, cued up travelogue after travelogue. I’ve even done a dive deep inside the dust-encrusted pages of my Rand McNally Atlas of the World.

But no matter how much research I do, I can’t come up with a location that people seem more confused about than Rhode Island, the pocket-sized slice of New England that my wife and I have called home for more than forty years.

Everyone, of course, can rattle off the fact that we are small. But it is grueling work to explain that we’re not actually an island. That we have nothing to do with Martha’s Vineyard. And that we don’t stretch out into the Atlantic right next to New York.

Delusions like these drive us Ocean Staters crazy. But over the last few decades of working as a travel journalist for newspapers and magazines, I’ve stumbled on a vein of muddled thinking that is far, far worse.

If you’re not a traveler, I am sorry to inform you that many Europeans, Asians and South Americans — those who live on just about every continent — cling to some eye-popping misconceptions about the Ocean State.

The city of Providence, too, I’ve discovered, brings out associations that are, at best, colorfully weird. At worst, they’re just plain nuts. This has stayed true, no matter whom I’ve interviewed. No matter where I’ve traveled.

To be fair, at least a few of these ideas have seemed sort of understandable. A South African safari guide from the Sanbona Wildlife Reserve insisted to me that Rhode Island was founded by Cecil Rhodes, the mining magnate who created the former African country of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia).

Hmmmm, I thought. Not exactly. But a nice try.

A New Zealand sheep farmer I interviewed in the scenic but remote outpost of Waipukurau claimed that being small “inspired Rhode Islanders to construct one of the globe’s largest buildings.”

Was he thinking of our State House? I asked (having read that it boasts the fourth-largest self-supported marble dome in the world).

“No, no,” he replied. “Your Superman skyscraper.”

Since I’m a proud Providence resident and a longtime worrier about the possibility of losing that art deco landmark, it took me a while to recover from finding out that it was famous abroad.

Other impressions of Rhode Island I’ve collected during assignments over the years have been nothing short of absurd.

After we’d chatted pleasantly for a while, a souvenir seller in the central square of Cusco, Peru, told me this: “I have a coffee table keepsake of your island.”

This made me instantly curious. Especially when she showed me a clear plastic snow globe that was populated with palm trees. When you flipped it over, minuscule grains of sand sailed gently around and down to coat the tropical scene.

“Your home,” she continued, “it is the loveliest in the Turks and Caicos archipelago.”

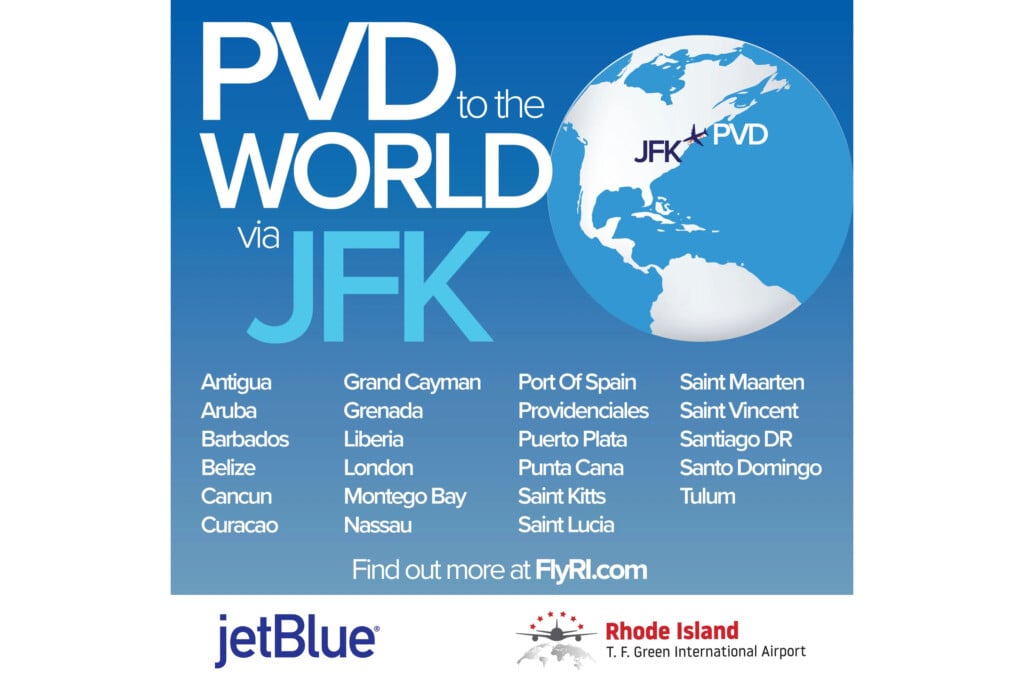

I put on the blandest expression possible. I edged over to another souvenir booth. It was only after looking it up that I realized she had confused Providence with the sun-soaked Eastern Caribbean island known as Providenciales.

Later on in my career, a middle school teacher in Hikone, Japan, bought me an oversized can of Sapporo during a Kyoto-to-Tokyo hike I was writing about. After we drank in silence for a while, he told me the following: “Blues music, and even bluegrass, was invented in your state. How do you Rhode Islanders prefer to dance?”

Although I’m well aware of the iconic Newport Jazz and Folk festivals, this didn’t seem like information I could trust. Still, since I tend to duck under the nearest table whenever a band strikes up, I said nothing. I didn’t feel qualified to reply.

And then there was the bartender in Brussels, Belgium, who acted as if he had met an old friend when I asked his opinion of tourists he’d served from different countries, including the U.S. He wiped off a wine glass and nodded sagely after I told him where I was from.

“Of course,” he replied. “The state known for its cheese.”

This turned out to be the last straw.

Please understand that I’ve nothing at all against the feta or mozzarella that’s made in Rhode Island. In fact, I think our fromage (as the bartender put it) is nothing less than world class.

But why hadn’t anyone in the far-flung places I’d traveled to heard about the things my state is actually famous for? Our sailing traditions. Our history of religious freedom. Our gargantuan quahogs. Our nationally recognized appetizer, calamari.

I’d asked again and again, both as a reporter and as a person who loves where he lives. Nada, was what I’d gotten back. Niente.

Nothing at all.

For more than a year, thinking about the sheep, the snow globe, the bluegrass and the cheese, I succumbed to a sense of deepening despair.

This, despite the fact that people all over the globe tend to speak excellent English. And that in many countries, residents don’t graduate from grade school until mastering geography to a degree that should make us Americans jealous.

Back when I had interviewed the New Zealand farmer, I’d complimented him on that country’s sheep (and, to be honest, its legs of lamb as well). Eager for a kind word in return, I’d gone as far as to mention the formidable, widely admired Rhode Island Red rooster.

The guy furrowed his sunburned brow. He wiped off the inside of his cap.

My well-informed and friendly farmer drew a complete blank.

I was doing my best to tell accurate stories, I thought, about territories and towns from the Far East to Egypt to the Galapagos. I’d even written about Antarctica and had worked to learn everything I could about the White Continent before putting pen to tablet.

How could it be that the locals I’d been talking with for quotes and story background seemed perfectly happy to toss off the most slapdash, the silliest imaginable misconceptions about my home?

After indulging myself with this streak of self-pity, a quiet, small voice in my head (or, it might have been the voice of my wife) brought me around.

I realized that I was guilty of misperceptions about places I hadn’t visited that were dramatically worse. Worse than the farmer’s or the bartender’s, or the woman selling souvenirs.

Before traveling there, I’d thought Greenland was a place of small but sturdy horses, and that Iceland hosted a massive sheet of glaciers — instead of the other way around.

I believed the Red Sea was so named because of a serious seaweed issue. And — I’m especially embarrassed to admit this — I assumed the Russian steppes required travelers to increase their altitude from one field or forest to the next.

Did this glimmer of self-awareness make me feel better? Unfortunately, it did not. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t be anything other than a homebody who, for his job, happened to be everyplace on Earth except at home.

And then it happened. It was toward the end of an assignment in Istanbul, Turkey, writing about a kind of public bath and traditional spa known as a hammam.

One cheerful spa manager struck up a conversation with me in English as I emerged from under searing suds of olive oil soap and clouds of cumulous steam.

The whole place felt dreamlike, with stars and moons depicted in a mighty dome of a ceiling. In fact, I could have been dreaming.

But what I heard next was absolutely clear. The man asked where I was from and I told him, expecting the usual. But what I’d gotten back was new.

And to my delight, it wasn’t muddled at all.

“Providence, Rhode Island,” he mused, just as a wisp of steam floated past, spidering up to the starry ceiling. “Providence. Rhode Island. It sounds to me like the most beautiful place in the world.”

_________________________

Peter Mandel is a travel journalist for The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times and National Geographic Kids, and an author of books for children.