From the Archives: Adrian Hall’s Long Goodbye

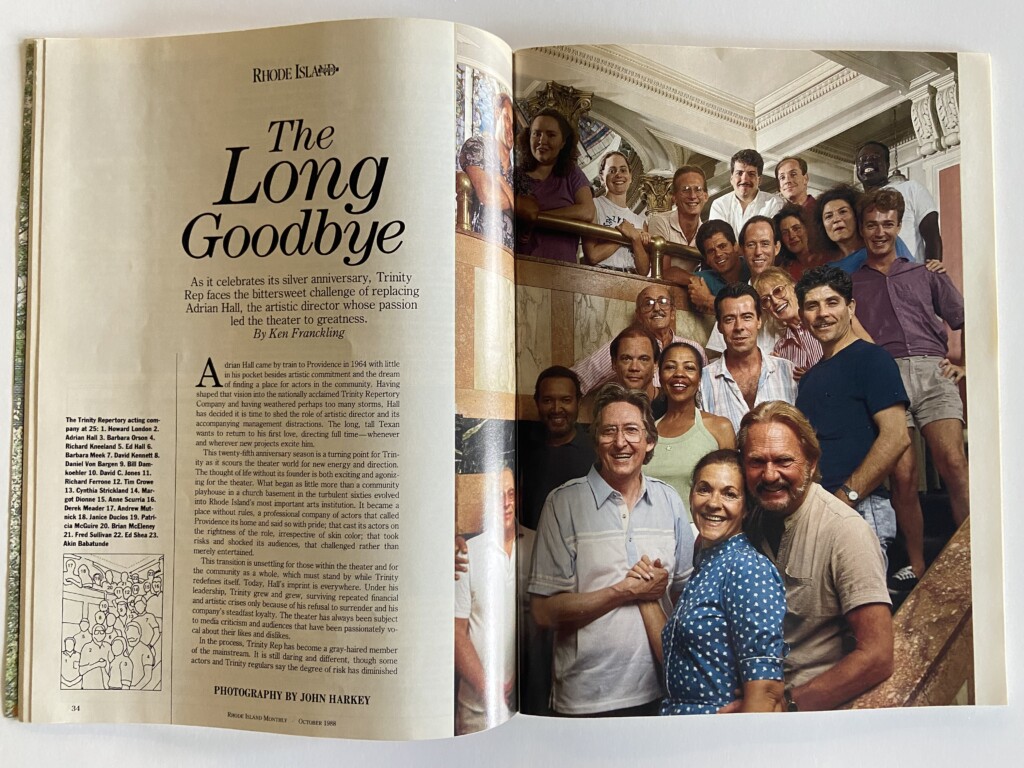

As it celebrates its silver anniversary, Trinity Rep faces the bittersweet challenge of replacing Adrian Hall, the artistic director whose passion led the theater to greatness.

Editor’s note: As we celebrate our 35th anniversary, we’ll be publishing articles from our archives from time to time. This story first ran in the October 1988 issue of Rhode Island Monthly.

Adrian Hall came by train to Providence in 1964 with little in his pocket besides artistic commitment and the dream of finding a place for actors in the community. Having shaped that vision into the nationally acclaimed Trinity Repertory Company and having weathered perhaps too many storms, Hall has decided it is time to shed the role of artistic director and its accompanying management distractions. The long, tall Texan wants to return to his first love, directing full time-whenever and wherever new projects excite him.

This twenty-fifth anniversary season is a turning point for Trinity as it scours the theater world for new energy and direction. The thought of life without its founder is both exciting and agonizing for the theater. What began as little more than a community playhouse in a church basement in the turbulent sixties evolved into Rhode Island’s most important arts institution. It became a place without rules, a professional company of actors that called Providence its home and said so with pride; that cast its actors in the right kind of the role, irrespective of skin color; that took risks and shocked its audiences, that challenged rather than merely entertained.

This transition is unsettling for those within the theater and for the community as a whole, which must stand by while Trinity redefines itself. Today, Hall’s imprint is everywhere. Under his leadership, Trinity grew and grew, surviving repeated financial and artistic crises only because of his refusal to surrender and his company’s steadfast loyalty. The theater has always been subject to media criticism and audiences that have been passionately vocal about their likes and dislikes.

In the process, Trinity Rep has become a gray-haired member of the mainstream. It is still daring and different, though some actors and Trinity regulars say the degree of risk has diminished in recent seasons. But now it is blessed with a solid financial base and respect from the establishment — including in the 1981 special Tony Award, the industry’s highest honor, for excellence in regional theater.

“There aren’t many institutions like this. Trinity is a very special case because of Adrian’s extraordinary stature as a stage director,” said Rob Marx, who directs the theater division of the National Endowment for the Arts, a crucial financial backer of Trinity from the beginning. “With Adrian’s leaving, it is now up to the institution he has created to decide how it wants to proceed, how the company wants to proceed, what it wants to be after Adrian leaves.”

The search for a new artistic director couldn’t come at a more opportune time. “The Young Turk” resident theater companies that began in the fifties and sixties as an alternative up the monied glitz of Broadway and managed to survive — places such as Trinity, the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C, the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, and the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis — have reached middle age. There is a lot of reexamination to make sure they don’t become stodgy and dull.

“It seems coincidental to me that Adrian’s departure comes at this time. Personally, I find it to be a very exciting prospect, not only for this theater, but for theater all across the country,” said actor William Damkoehler, who joined Trinity fresh from Illinois State University in “The theaters have become very institutionalized, which is to their credit, and must be reexamined again. The fact that we’re not alone in this is a great comfort. I think that the community itself is going to become excited, too, as the next few years develop.”

To understand what Trinity trustees and company members are looking for in a new artistic director, one first must look at the role this theater has played not only locally, but in the vanguard of American theater since Hall brought his lively experiment to Providence.

An Ancient Craft Almost Lost

Hall sat one morning in his East Side living room reflecting on the necessity of taking legitimate theater outside of New York. He spoke with great animation about “that stinging, angry thing that I felt: that the artist was the least respected or connected to the institution.” His hands sliced the air in emphasis, the words zipping out as they tried to keep up with his thoughts.

“There was a formula way for making money out of the performing arts. It became so special and so tied into making money that success was judged by when. or it made money. Gradually, it lost its ability and went on to grosser and less complicated things,” Hall said. “This old craft, this ancient craft that had been practiced for a thousand years almost the same way, almost died.”

His vision from the start was to build a devoted core of actors who would live in the community and create a following, at the same time forging an on-stage chemistry, not gypsies who bounced from city to city, stage to stage. It was done for love, not money. In the early days, the pay was as little as $50 a week. Now, the Actors Equity union scale at Trinity is in the range of $420 to $600 a week — hardly money to get rich on.

“There is a grim, ugly little facet of our country that believes there is something noble about sacrifice. Somehow we have never felt that the artist had a right to demand a place in the community,” Hall said. “If there is to be a rich culture for the future, we can’t be shoved in the corner anymore.”

Barbara Orson was already in Providence when Hall was brought in for the experimental 1964 season. She had left the New York theater scene for marriage and motherhood and was unsure whether she’d get much chance to act again on the professional level. As a founding member of Trinity Square Playhouse, she was cast as the lead in Hall’s first Trinity production, Tennessee Williams’s Orpheus Descending. She’s done more than eighty-five productions since.

“It was the right time for us, and he certainly was the right man for us. This theater wouldn’t be, were it not for Adrian Hall. The kind of ingenuity, inspiration, adventurousness, the kind of people he brought in, the materials he selected, his relationship to the community even when it was at its worst moment was important because it galvanized and it interested and it shocked, all things like that were very important,” Orson said.

Richard Kneeland, William Cain, Vincent Gardenia and Katherine Helmond were among the first out-of-town actors Hall summoned to Providence. The core out of which Trinity grew still includes Kneeland, Orson, Peter Gerety, Barbara Meek, Timothy Crowe, Richard Jenkins, Ed Hall, Daniel Von Bargen and David Jones. Richard Kavanaugh’s sudden death in August was the most wrenching loss the company has suffered to date.

Kneeland said the opportunity to work with other actors for such an extended period of time is truly remarkable. “It is incredible in the American theater what has happened here. Family is the word that always springs to mind, but it is more a sense of dynasty, of a unity that goes beyond family,” he said.

Exposing Youth to Theater

Trinity’s initial subscription audience totaled two hundred. It peaked at more than 20,000 in the 1986-1987 season. One-third of today’s subscribers credit their first exposure to the theater to Project Discovery, an innovative NEA program that had its greatest success in Rhode Island. It brought every Rhode Island high school student to Trinity performances four times a year at the Rhode Island School of Design auditorium from 1966 to 1969.

“It got to a point where it overwhelmed us, when we had an extra 40,000 people for every play,” said Marion Simon, Hall’s devoted assistant for the past two decades. “It was a wonderful thing that happened, and it is good that we could integrate it into what we are.”

School districts or students now finance the trips themselves, and about 20,000 students are involved annually. “The young people are exposed to theater before they’re afraid of it, before anybody tells them it’s really not for them,” Simon said. “It has been a wonderful audience development phenomenon. Without it, we would be nowhere near what we are today.”

Orson keeps running into Rhode Islanders in the theater profession — actors, directors, writers and backstage workers — who tell her their careers were inspired by Project Discovery.

Trinity moved into the 1970s with both acclaim and controversy over its provocative brand of theater and unconventional staging that resulted from the collaborations of Hall and set designer Eugene Lee, who created special environments for each play, sometimes interspersing the action among the audience.

The company tackled Robert Penn Warren’s Brother to Dragons; John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men; the Adrian Hall-Timothy Taylor collaboration, Son of Man and the Family, a musical about the Charles Manson killings; and an adaptation of the James Purdy Depression-era novel, Eustace Chisholm and the Works.

In 1975, Edwin Wilson of the Wall Street Journal called Hall “a man of vision and imagination worth ten pedestrian directors.” After Eustace Chisholm, mainstream Providence was calling him other things. The play’s 1976 debut offended some because most of the action took place on a bed, the work had a homosexual theme and an on-stage abortion scene. It was either the catalyst or excuse for Trinity’s board of trustees to fire Hall. Backed by the entire company, Hall turned around and “fired” the board of trustees, setting up a new board to oversee the company.

In her fourth-floor office at the Lederer Theater on Washington Street, Simon has filed records of that turning point under ‘putsch.’ “It was terrible, really. But this nice group of people who had been on the board were incapable of raising money,” Simon said. “And to get away with that, they had to blame it on Adrian or the material or Eustace Chisholm and the Works or the Son of Man and the Family, blame it on anything except their inability to raise money.

The solidarity sent the actors to area malls to pass tin cans for donations and sell T-shirts. With a new, sympathetic board in place, Trinity limped ahead with determination but shaky finances.

By the spring of 1979, the non-acting staff were laid off for five weeks to cut costs. The Internal Revenue Service was ready to seize the personal assets of Hall and business manager David Black for failing to pay the government an estimated $100,000 in withholding taxes, which had been used illegally to keep the actors on the payroll.

Hall and E. Timothy Langan, who soon succeeded Black as business manager, went to businessman Bruce G. Sundlun and asked for help straightening out Trinity’s mess — a $408,000 deficit and no credibility in the financial community. The Outlet Communications Company chairman and then-chief executive officer put his clout to work only after Trinity showed it could operate more efficiently and increase revenue, which it did by raising ticket prices from $8 to $10. He then arranged loans to satisfy the Internal Revenue Service and put together a seven-year plan to eliminate the deficit. It was paid off in three years. An engraved copper urn, holding ashes symbolizing the deficit, sits on a shelf in Sundlun’s downtown office, a gift from Trinity.

“I was impressed by Adrian and Tim’s sincerity and desire to keep it going. They had an organization of great actors and actresses and felt it would be wrong for it to go down the tubes,” Sundlun said. “I didn’t blame them for the financial condition they were in because that was not their training or their skill. They weren’t dishonest. They just didn’t have any experience in business management. I did, so there was something I could help them with. I told Adrian, ‘We are going to establish some rules: I will never tell you who to put on or what not to put on or how to put it on. That is completely your province. Conversely, we are going to set a budget and we’re going to run the financial side of the house and you are going to stay out of that.’ The rules we laid out in those early meetings worked, and they’re still working and they’re fairly fundamental.”

Sundlun, soon named Trinity’s board chairman, also set up a lucrative bonus system in the range of 30 to 50 percent for top managers who keep within their budget and implemented a fringe benefits program for all Trinity employees, improving on minimal coverage that Actors Equity required only for the performers.

“From 1979 on, we never had an unprofitable year,” Sundlun said. “Revenues exceeded expenses. We generate from pure theater operations about 72 percent of our expenses. The rest of our money gets through contributions and grants.” Most nonprofit theaters are in the 60 to 65 percent range, though a few are even higher than Trinity.

Hall’s commitment to a true resident company received a ringing endorsement 1984 with a first-in-the-nation NEA ensemble grant to guarantee up to twenty-five actors, designers, and directors ten-month contracts that meant financial security in a business where unemployent hovers around 90 percent.

Sundlun spearheaded a three-year challenge grant drive that ended in May with $1.64 million to support building improvements and the beginnings of a permanent endowment fund. Completion brought the company a $350,000 matching grant from the NEA.

“We barely made it under the wire. In the last thirty days, I went back to the bigger corporate givers in the community and said, ‘Hey, we’ve come a long way but we’re $72,500 short. I’ve got to ask you for another bite.’ Nobody refused me. Everybody came through with varying amounts, from $1,500 to $25,000.”

First Step: Providence to Dallas

Hall’s withdrawal from Trinity actually began in 1983 when he simultaneously became artistic director of the Dallas Theater Center. Kneeland compared that decision to “your father taking a mistress: ‘Well, I guess he doesn’t like us very much.’ When you got tired or angry or bitter, there was that. But I know geography made no difference. He was on the phone every day and any problem was made known to him, no matter where it was. It was his step before the last step, of needing a new stimulus in his life.”

The Dallas distraction helped make Langan more of a leading player in the Trinity administration. Working in professional theater since age fifteen, he is now, at thirty-six, as strong a force on the business side as Adrian is on the artistic side. The Trinity budget has grown from $1.1 million to nearly $4 million since he took over as managing director in 1979.

“In this theater, the founder is an artist, so Adrian is very much the more equal of this partnership. That is probably going to shift somewhat. I don’t think Adrian and I could ever find a way to work as a completely equal partnership. This is his family, his toy, his baby, his dream. It is just different in that way. You just can’t lose that imprint,” Langan said.

Hall said he also will pull back from his duties in Dallas, for the same reason he is leaving Trinity. “I feel what I have really done is set the agenda for institutions in this country, and now I’d really like to pursue being an artist,” he said. “Drying up is a fear that all artists have.”

At an August retreat for Trinity trustees, Hall told them informally that he wanted to begin phasing himself out as artistic director. When word got out to the press, the gradual withdrawal was transformed into a full-blown search for a successor, complete with timetable.

Trustee Robert D. Higgins, president of Fleet National Bank, was named chairman of a search committee comprised of Hall, Langan, other trustees, and Trinity actors Orson and Damkoehler. Before posting the “help wanted” sign, a subcommittee visited other resident theaters around the country and discovered there are not a lot of precedents that apply to his transition.

While Hall made the resident company the hallmark of Trinity, other regional theaters have found other points of distinction. Jon Jory at the Actors Theatre of Louisville focused on finding exciting new plays. The American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge turned to nontraditional productions that introduced new forms of the term. At Washington’s Arena Stage, Zelda Fichandler brought obscure plays and unknown directors to an audience more interested in surprises than commercial theater.

“One of the issues which is slightly different at Trinity than maybe other theater companies is a commitment to a resident company. It exists at the board level, in Adrian’s mind, and within the artistic company. It is a clear and unqualified commitment,” Higgins said. “It’s not just the actors, it’s the whole ensemble — the technicians, the set designers — it’s a well-oiled machine. I don’t mean to be mechanical about it. It should serve as an attraction to the right kind of person. If not, they’re probably not interested in Trinity, and we’re probably not interested in them.

“We’re making a large step in this transition. We ought to feel free, and the theater should feel free, to open up the windows and let some air circulate around that isn’t identical to the kind of management direction that Adrian provided, although that was clearly outstanding.”

Higgins said the search committee, assisted by arts management consultant Gregory Kandel of Greenwich, Connecticut, had hoped to find a new artistic director by the end of this calendar year with that person to begin work next September. But the process is more likely to take another couple of years, allowing time for the candidates on the “short list” to work with the company before a decision is made.

“We all agree on the need to get the best possible talent available in this country or outside, theoretically, for that position,” Higgins said. “Adrian is honestly approaching this on the basis that this is something he was instrumental in creating, and he wants to leave a legacy of an organization which is run successfully, has top-quality artistic direction, and continues to be a resident company, which is really one of the linchpins of the organization. Adrian is the real plus in this situation. He has committed to stay at Trinity until an acceptable replacement for him is found and in place. That gives us a lot of flexibility.”

Sundlun, Langan and Higgins all stress that the board is making it clear to every candidate that the trustees have not and will not interfere with the company’s artistic direction. Still, the imprint of Adrian Hall looms large over potential successors.

What Size Shoes to Fill?

“I’m sure every director in the country, if not the world, would love to be the Number Three artistic director at Trinity Repertory Company,” said Garland Wright, who in June 1986 became the Guthrie Theater’s sixth artistic director in twenty-five years.

While the Guthrie has been firmly committed to the classic plays, only Wright’s recent hiring renewed the resident company dream of the founding director, the late Tyrone Guthrie.

“Here at the Guthrie, one thing that was very helpful in the transition for me was that the board and the organization was willing to totally redefine itself,” Wright said. “That takes a lot of courage, particularly when you’ve got something that is very healthy. To allow it to renew itself is the nature of making art and theater.”

At Trinity, aside from proven talent and ability, Damkoehler feels the search must settle on someone who is “an exciting artist. Everything is set up for that person to come in and do creative things. Probably the biggest battle will just be following Adrian Hall. Those are big shoes to fill. I know all of the candidates have it at the back of their mind, but those we are looking at certainly are capable of filling them and getting right to work.”

Sundlun said he finds the selection process refreshing and positive in contrast to some he has witnessed in the corporate community. “My experience is that changes in chief executive officer are most often delayed, hindered, or impaired by the CEO himself, who chooses not to leave or tries to dictate his successor. Adrian’s attitude was most positive,” Sundlun said. “He recommended that the time had arrived for the theater to look for a new artistic director, and he made it very clear that the new artistic director should not be, in his words, ‘a clone of Adrian Hall.’”

Hall will leave with a pension agreement established several years ago and the right to return and direct an occasional play — “not necessarily major plays, but something that would perhaps not otherwise get done.” He also will oversee an archive that will document Trinity’s history for reference and active use. “My goals, while they seem strident, are really to preserve what we’ve created here,” Hall said.

Simon doesn’t plan to stay on at Trinity after Hall leaves. She also doubts many directors would want his job because of the sacrifices it requires.

“First of all, you give up all of your creative need. Most of the time, you’re handling administrative problems, granting problems, fundraising problems, community problems, casting, producing. You become a producer. The greater the director is, the less he wants to become a producer,” Simon said. “What makes a difference is whether the person can give up enough of his or her own creativity to be that generous and deny yourself on that level as an artist. It really is a great contribution.”

Ever since Hall began splitting his time with Dallas, a subtle uneasiness has spread among the company and Trinity’s audiences. His impending departure has actors wondering what the future holds for them here. In spite of the board’s commitment, Kneeland, for one, is pessimistic about the future of this particular resident company.

“I like living in Rhode Island and would wait and see who took it over, but I would never believe it could happen again,” he said. “Any director who takes over is going to have his own favorite, dependable artists. I totally respect that. I can always come back here and do a play because I have a lot of people in the city who like to see me on the stage. I’m in a state of flux, too. I’m taking every serious offer I get lately. I would give anybody my time and my interest for as long as it was working, but I don’t see a future livelihood here.”

Orson is more hopeful that the Trinity company will click under new direction.

“We’re hoping that new and young talent will come in here and we will have the possibility of someone who is here all of the time, here for us. Adrian is so special, but we were lucky,” she said. “And we hope we will hit it right again. I think because of the kind of company, the kind of people we have here, and the kind of audiences we have, they will be looking forward to a new era. And I think we must look forward. Adrian Hall will be a tough act to follow, but it’s time.”

Marx, of the NEA, said the next director will have an entirely new challenge. “He will be inheriting a company, a way in which a company works, he will be inheriting a history. There is a large institution there now. The next person will have to understand how to use those tools that Adrian provided.

“You can’t be a creative individual, you can’t be a creative institution if you allow yourself to fall into a rut. There has to be constant change: new ways of dealing with problems, new ways of communicating with an audience.”

In a profession where egos work overtime, Hall talks of the actors and their place in Trinity as superseding the importance of what he has done. “People think I’m concerned about keeping the specter of ‘Adrian Hall’ over everything, but I’m not,” he said. “I’m much too proud of Trinity Rep — for what it is — to want my name on it.”

Adrian Hall wants the new director, whoever he or she may be, to know something else.

His shoe size is 9½ B.

“It’s a very average foot. It’s not a big foot at all.”